subscribe to our mailing list:

|

SECTIONS

|

|

|

|

Life on Mars? The real lesson from Lowell

By Andrea Bottaro

Posted March 17, 2006

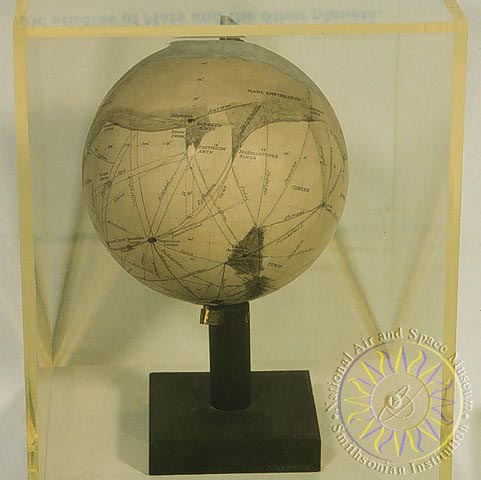

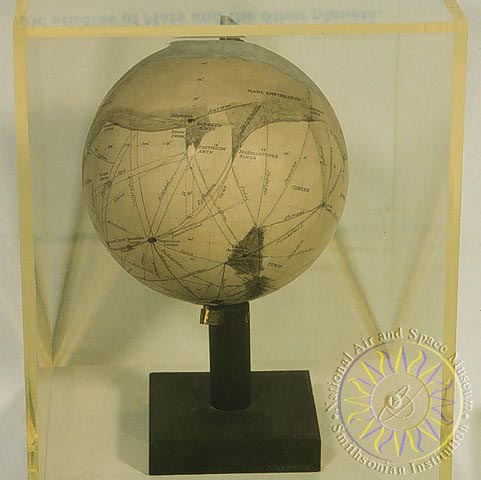

In an almost comical display of lack of self-awareness, Jonathan Witt of the Discovery Institute has recently taken inspiration from Google’s homage to Percival Lowell, the 19th

century astronomer who argued for the existence of a system of

engineered channels on the surface of Mars, to extract from this

glorious scientific blunder the lesson that science moves, at times,

“backwards”, i.e. rejects apparently established theories for more

traditional, often religiously inspired views (something that Witt

clearly wishes would happen far more often). In an almost comical display of lack of self-awareness, Jonathan Witt of the Discovery Institute has recently taken inspiration from Google’s homage to Percival Lowell, the 19th

century astronomer who argued for the existence of a system of

engineered channels on the surface of Mars, to extract from this

glorious scientific blunder the lesson that science moves, at times,

“backwards”, i.e. rejects apparently established theories for more

traditional, often religiously inspired views (something that Witt

clearly wishes would happen far more often).

In addition to Lowell’s channels-on-Mars theory, Witt mentions in

his article the idea of a Universal Beginning and opposition to

spontaneous generation as other instances in which ideas originally

found in the Judeo-Christian tradition have at some point worked their

way back into the scientific mainstream. I’ll just pass on discussing

Witt’s rather simplistic ideas about modern cosmology and abiogenesis,

not to mention the history of science, since his arguments are just a

rehash of well-known ID and Creationist talking points that have been

abundantly critiqued before. I want instead to point to another

obvious, and far more topical lesson that Witt could have taken from

Lowell, but, alas, didn’t.

The most striking aspect of Lowell’s argument for the artificiality

of Mars’s “channels” is, in fact, its uncanny resemblance to modern

arguments for the intelligent design of biological structures. Luckily

for the interested reader, Lowell’s first book on the subject, titled

simply Mars, seems to be the object of some sort of cult following, and can be found online in its entirety (chapters 4 and 5 are the most relevant to the discussion here). For any ID connoisseur, reading Lowell’s original arguments is an exercise in dèjá vu (eat this French, Berlinski!), since they are an almost perfect example of design inference as currently practiced by ID advocates.

Essentially every fallacy of modern ID inferences can be found in

Lowell’s book. You will find confident claims about the manifestly

non-natural basis of the observed structures:

... the aspect of the lines is enough to put to rest all the theories

of purely natural causation that have so far been advanced to account

for them. This negation is to be found in the supernaturally regular

appearance of the system, upon three distinct counts: first, the

straightness of the lines; second, their individually uniform width;

and, third, their systematic radiation from special points.

...

Physical processes never, so far as we know, end in producing perfectly

regular results, that is, results in which irregularity is not also

discernible. Disagreement amid conformity is the inevitable outcome of

the many factors simultaneously at work.

...

That the lines form a system; that, instead of running anywhither, they

join certain points to certain others, making thus, not a simple

network, but one whose meshes connect centres directly with one

another, is striking at first sight, and loses none of its peculiarity

on second thought. For the intrinsic improbability of such a state of

things arising from purely natural causes becomes evident on a moment’s

consideration.

...

Their very aspect is such as to defy natural explanation, and to hint

that in them we are regarding something other than the outcome of

purely natural causes.

You will find references to diagnostic features of basic human design, and analogies with known designed structures:

That the lines should follow arcs of great circles, whatever their

direction, is as unnatural from a natural standpoint as it would be

natural from an artificial one; for the arc of a great circle is the

shortest distance from one point upon the surface of a sphere to

another.

...

In fact, it is by the very presence of uniformity and precision that we

suspect things of artificiality. It was the mathematical shape of the

Ohio mounds that suggested mound-builders; and so with the thousand

objects of every-day life.

(I can almost hear Behe arguing about Mt. Rushmore!)

Specious mathematical/probabilistic arguments and analogies are there too:

Simple crossings of two lines will of course be common in proportion

to the sum of an arithmetical progression; but that any three lines

should contrive to cross at the same point would be a coincidence whose

improbability only a mathematician can properly appreciate, so very

great is it.

...

Of course all such evidence of design may be purely fortuitous, with

about as much probability, as it has happily been put, as that a chance

collection of numbers should take the form of the multiplication table.

Strikingly, you will even find claims that the “overhelming impression of design” is prima facie evidence of actual design:

Their very aspect is such as to defy natural explanation, and to

hint that in them we are regarding something other than the outcome of

purely natural causes. Indeed, such is the first impression upon

getting a good view of them. How instant this inference is becomes

patent from the way in which drawings of the canals are received by

incredulously disposed persons. The straightness of the lines is

unhesitatingly attributed to the draughtsman. Now this is a very

telling point. For it is a case of the double-edged sword. Accusation

of design, if it prove not to be due to the draughtsman, devolves ipso

facto upon the canals.

Finally, Lowell knew he could not formulate a convincing argument

for design without tackling the fundamental issue underlying design of

any kind, that is, its purpose. Just like ID advocates who, in order to support their design inference, find themselves forced to conflate function with purpose,

so did Lowell have to justify the existence of this elaborate channel

system with some sort of anthropomorphic goal. He thus claimed that,

since Mars is clearly a dry planet, the existence of channels was

entirely justified as part of an irrigation system (indeed, he went as

far as describing the existence of putative “oases” at the intersection

points of the channels).

Now, Lowell’s argument about the “purpose” of the Mars canals was

clearly more far-fetched than most of the equivalent arguments of

modern ID advocates about the “purpose” of biological structures, but

one should keep in mind that Lowell, unlike Behe, Dembski, etc, didn’t

have the benefit of actual science providing convenient, empirically

tested functional explanations for his supposedly designed structures.

In fact, when faced with structures whose functional properties are

unknown, ID advocates do not fare much better than Lowell: for

instance, Jonathan Wells has claimed that since centrioles (which are

sub-cellular structures of unclear function that participate in the

cell division process) look superficially like man-made turbines, they

must be, and he built around this spurious assumption a whole fanciful

model of what teeny-weeny turbines could actually be doing in the

context of eukaryotic cell division.

Finally, if you are wondering how Witt could have missed the obvious

parallels between modern ID advocacy and Lowell’s “martian” design

inference, let me point to Witt’s vitae page on the Discovery Institute site,

where Witt proudly claims to have discovered the fallaciousness of

“Darwinism” after getting over all those pesky “arcane scientific data”

and “jargon”:

They claimed to rest their arguments on a wealth of arcane

scientific data, but once I dug past the jargon, I found that their

arguments were always built on a foundation of question begging

definitions, either/or fallacies, bogus appeals to consensus, and

quasi-theological claims that ‘an intelligent designer wouldn’t have

done it that way.

Still wondering?

|

|

In

In